If We Criminalise Ecocide, It Should Apply from Earth to Orbit

This guest blog is authored by Dr. Kai-Uwe Schrogl, President of the International Institute of Space Law (IISL), and Anna Maddrick, Legal Adviser on Climate Matters to the Permanent Mission of Vanuatu to the United Nations.

When we gaze into the night sky, we imagine an endless and unlimited cosmos. But a closer look reveals characteristics that offer comparison to the Earth’s environment: we see orbits, which are limited natural resources, we see irresponsible use, which has created masses of space debris, and we can witness growing competition about sites on the Moon and asteroids, as well as their exploitation.

The international community is struggling to manage these environmental issues effectively. As high-risk technological interventions expand - from orbital mega-constellations to solar geoengineering - the need for robust legal frameworks that extend beyond Earth becomes clear. Outer space and the Earth’s atmosphere are global commons and part of interdependent, complex systems. In both arenas, failure to regulate could push us beyond critical planetary boundaries. A stronger foundation in international criminal law is urgently needed.

Environmental stress in outer space

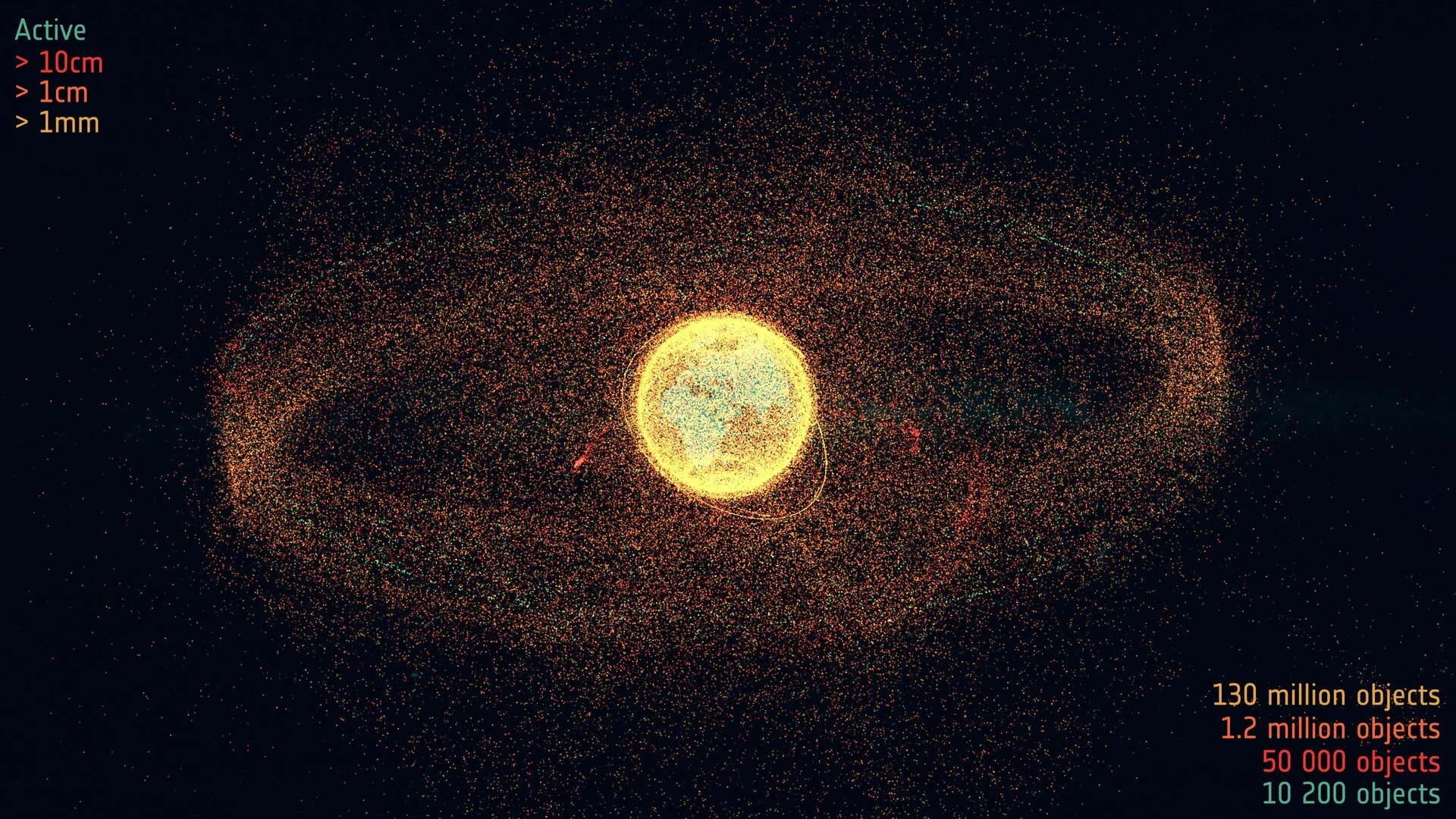

The near-Earth space environment is under severe and growing stress. This is documented in the annual Space Environment Reports of the European Space Agency (ESA). In the past ten years, human-made objects larger than 10 cm more than doubled to 35,000. Smaller objects go into the millions.

There are further challenges. Rocket launches as well as space objects burning up in the atmosphere create damage, which is not yet properly researched and assessed. Satellite constellations are causing light pollution - hindering astronomy but also robbing vast numbers of people of their cultural heritage: the ability to gaze upwards at the stars. Orbital positions in some altitudes have become scarce. Planetary protection from human contamination is so far only based on best practice. And in future, we will face questions on the environmental sustainability of extracting resources from the Moon and other celestial bodies such as asteroids.

“Satellite constellations are causing light pollution - robbing vast numbers of people of their cultural heritage: the ability to gaze upwards at the stars”

Credit: Ryan Jacobson/ Unsplash.

Existing space law is fantastic...

Contrary to what you might hear, existing space law is fantastic. Although created in the 1960s and 1970s, it has maintained its virtues and value. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 constitutes outer space, the Moon and other celestial bodies as a global common outside national jurisdiction.

Private actors require authorisation to operate in outer space and continuous supervision by their governments, based on the State responsibility and liability introduced in the Outer Space Treaty. This should happen through national space laws, though only a small, but growing, number of countries have enacted such legislation. The Moon Agreement of 1979, with fewer than 20 ratifications, remains a dormant but crucial regime awaiting activation - offering a legal pathway similar to the Law of the Sea for shared use of extraterrestrial resources.

The Outer Space Treaty is a treaty of principles. Attacking it as “obsolete” only serves the purpose of eroding the idea of space as a global common. Instead, we must build on its foundation, strengthening it with concrete norms and rules developed through the UN, soft law instruments and standards.

...but it desperately needs teeth

Millions of objects, largely space debris, in orbit – captured in August 2024.

Credit: European Space Agency.

It might surprise some to learn that for decades, breaches of space law were extremely rare. But today is different. The latest ‘space race’ has seen armed conflicts spilling into outer space, with the disabling of satellites and efforts to monopolise orbital planes through mega-constellations.

In this context, ecocide law - legislation that criminalises the most extreme forms of environmental destruction - could address three urgent gaps: the lack of law enforcement, the absence of harmonised responsibilities at national and international levels, and the failure to establish punitive consequences for environmental misconduct in space.

And there’s one more issue: public exclusion from space law debates. Decisions shaping our shared space future are largely made behind closed doors, with little civic oversight. Some private individuals now speak of colonising Mars as if celestial bodies are theirs for the taking - a notion fundamentally at odds with the shared, non-sovereign principles enshrined in existing space law. Broadening engagement could shift the conversation from one dominated by commercial interests to one rooted in stewardship.

Ecocide law could be a powerful instrument for outer space - and a safeguard against planetary manipulation

Space law needs an external catalyst - and ecocide law could be just that. The formal proposal led by Vanuatu and a coalition of small island states to amend the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court to include ecocide marks a turning point. The proposed definition - drafted in 2021 by an Independent Expert Panel - explicitly recognises outer space as part of the environment.

This opens the door to criminal accountability for environmentally reckless actions in outer space, from destructive anti-satellite tests to the unchecked deployment of polluting technologies or resource extraction regimes without due regard for future generations.

It also speaks directly to pressing concerns on Earth - such as the UK government’s recently announced funding of field trials for solar geoengineering, a controversial effort to reflect sunlight away from the planet by injecting aerosols into the atmosphere. Critics such as Raymond Pierre Humbert and Michael Mann have called such schemes a “dangerous distraction”, warning that they deepen systemic risks and governance failures without addressing root causes.

The parallels with space are striking. As with outer space, the atmosphere is a global commons. Both are subject to polycentric governance. Both face threats from unregulated experimentation by powerful actors. And in both cases, ecocide law could offer a uniform, enforceable framework - predicated on human rights and the principle of the Common Heritage of Mankind (CHM) - to buffer against catastrophic interventions, whether via rogue satellite debris or interventions that manipulate Earth’s life-support systems.

Our current moment requires us to think seriously about the governance of global commons, including those above our heads. While voluntary norms and soft law - non-binding agreements and guidelines —have shaped some responsible practices, they remain limited in enforceability. Ecocide law offers a way to reinforce these frameworks with meaningful accountability.

Establishing ecocide as a crime would help ensure that high-impact technologies - from geoengineering to space exploitation - are developed within ecological limits. These interventions affect complex and often poorly understood systems, with consequences that can reach far beyond national borders - and even beyond Earth. As pressure mounts - from escalating climate impacts to a renewed space race and the rush toward untested technological frontiers - ecocide law offers a vital legal safeguard: protecting our common heritage from irreversible harm and reinforcing a duty of planetary stewardship alongside innovation.